Don’t Look Back

By Terry Cavanagh, Distractionware, 2009

Play online (flash)

Free standalone version (Windows 5 MB, Mac 9 MB)

Prince of Players, Pawn of none

Everyone is familiar with the myth of Orpheus who wandered into the land of the dead to retrieve his beloved Eurydice. How the gods were moved by his song and allowed them to return to the world of the living under one condition - that they never looked back on the way up and away from this falle place. But with only a few steps left, Eurydice could not help but cast a final glance at her dear hometown, Sodom, and in that moment she turned into a salt statue.

It's not surprising that Terry Cavanagh based his bare-bones platform game, Don't Look Back, on the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Few myths have exerted the same appeal on, above all, artists and composers (who are particularly flattered by it). And although I can't think of any off the top of my head, the myth has almost certainly been used before in computer games as well. As I said, everyone knows the story. If you happen to mix it up with another one, it's because the motif “don't look back” is found in more mythologies than the Greek one.

The universal nature of the theme suggests that it holds a deeper meaning that is applicable to all humans, possibly even a moral lesson. But why is looking back portrayed as dangerous? Is it simply an illustration of the danger of looking down when you're balancing on a plank 300 meters above the ground? How easily you lose the race if you lose focus on yourself and glance at the runner on the track next to you?

Alternatively, the warning could pertain to something other than the action itself. A reminder that it can be dangerous to be too curious, that we shouldn't fall for temptations? A serious admonition to obey the gods blindly even when they give strange commands whose meaning we don't understand? Or is it a psychological observation of how hard it is to obey the command “don't think of a white bear”?

And what does Terry Cavanagh want to convey with his version of the myth in this game? We’ll have to return to that question. I don’t claim that he succeeds or that it even matters whether he does. But the game's connection to the “don't look back”-motif may be compromised if you know the events in advance. If you haven't played the game but want to experience it as it is meant to be experienced, it's therefore best to avoid reading about the plot beforehand.

Distraction he wanted, to destruction he fell

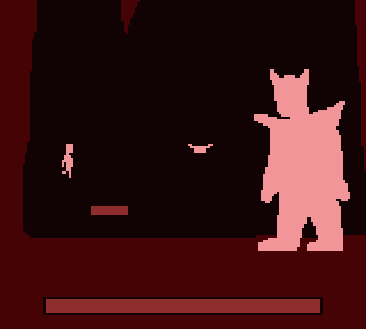

Is it worth your time then? It depends on your preferences for jump-and-shoot platform games, as well as your skill level and temper. The game is not large but tricky and frustrating in certain areas. The final boss battle with Hades, in particular, proved to be a test of my patience. But you restart on the screen where you die and you have an unlimited number of lives at your disposal, which is a welcome deviation from pure retro gaming.

There is no doubt that “Don't Look Back” is a competent representative of its genre. The movements are fast; the control, precise and satisfying (to the extent that it is possible with a computer keyboard). It is a nice feeling to shoot and outsmart the enemies.

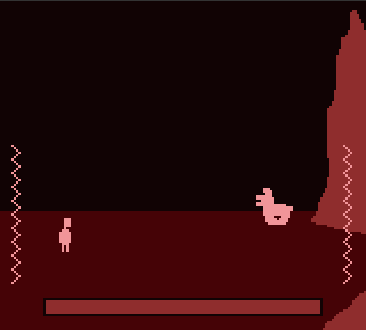

Graphically, the game is a clear homage to the Atari 2600, and a particularly successful one, despite the limitation of using only four colors. While the Atari 2600 was known for its large color palette, few 2600 games from that era are as visually striking and atmospheric as this one. Had it been released in 1981, it would have undoubtedly been considered a classic. But in fairness, it should be noted that Cavanagh would not have been able to achieve this on the original hardware. The size of some sprites, the rain, and the visual variety would have been technically impossible (at least all together in a working game).

The same applies to the sound and music, which probably uses at least 100 times more memory than a 2600 cartridge would have allowed. The sound effects, high-quality samples, are well chosen and make the bosses seem more threatening than graphics alone would be able imply. The two-voice, simple string arrangements with a melancholic, fateful tone perfectly complement the game's event. And even though it may sound like 80s synth strings, it is actually 80s FM synthesis à la Yamaha DX7, and thus far exceeds the attempts at string imitation made by the sound chips in 80s game consoles.

As I often find when playing classic or neo-classic games, it is strikingly easy it to shake off expectations from decades of technical and visual achievements. While testing Don't Look Back, I also played another game based on Greek mythology, God of War for PS2. The boss battles in that game were visually and audibly spectacular, with explosions of color and sound coming from every direction. Yet this encounter with Hades' three-headed dog, represented by 20x25 monochromatic light pink pixels, was equally as thrilling. My pulse raced and my imagination was stirred just the same. Its unique shape and double the number of pixels compared to the routine enemies was all it took for the boss sprite to leave a lasting impression, evoking a sense of accomplishment and the feeling that something significant was happening.

When will he come up for air, will anybody ever care?

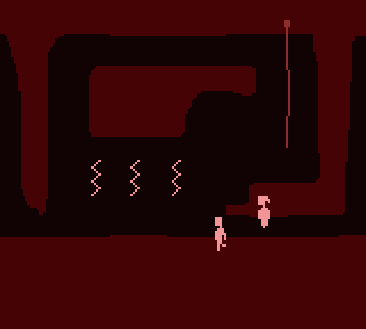

The game begins with a somber scene, as you stand at a grave and pay your respects. As you turn around and begin your journey, running from screen to screen, you quickly come across a weapon. From there, you descend into the underworld and encounter a host of enemies, including spiders, bats, and snakes. Navigating through the underworld requires jumping on disappearing platforms, dodging lava, and overcoming abstract power fields. The platforming elements are reminiscent of classic 80s games like Jet Set Willy and Pitfall 2, but the overall feel of the game is most similar to the flip-screen Ghosts 'n Goblins.

After a series of intense boss battles, you finally reach your deceased girlfriend. The path back to the world above is a different one, with no enemies to fight but fraught with an abundance of obstacles that are further complicated by the constraint of not being able to retrace your steps – or even turn and look back. There is no explicit warning provided, and while it may seem that the title and the setting of the drama should have prepared you, it actually works the opposite way. Without prior knowledge from reviews of the game, it is unlikely that you would take it for granted that the dozen jumping and shooting pixels represent Orpheus. Not until you save your girlfriend and for the first time mindlessly turn right and see her disappear in a haunting scream, do all the pieces fall into place. Now you understand where you are and why the game is called Don't Look Back. Now you understand that the final boss was Hades, that the dog was Cerberus, and that its large, weird head was supposed to represent three smaller heads.

It is a powerful moment that gives resonance to what has so far been mostly a minor pastiche, albeit one that is sleek and well-executed. It is a powerful moment that imbues the game with a deeper sense of meaning, elevating it beyond a mere pastiche. Furthermore, it highlights the challenge of following the gods' warning. Initially, one repeatedly makes the same mistake, driven by the natural instinct to flee from danger. And when faced with a dead end, there simply is no other option. As a result, your empathy towards Orpheus deepens.

But the game's major plot twist remains and, as is befitting, it also sheds new light on what has happened before.

As you eventually see the sky again, you quickly move on to the place where the journey began. The anticipation of a sense of accomplishment and a potential reward is palpable. But when you reach the grave, there is a man there. He is identical to yourself and stands just as you yourself stood there at the beginning of the game.

For a brief moment you stand there with your girlfriend. You stand in silence, staring at the man standing at the grave. Suddenly, a scream is heard, and you and your girlfriend vanish. The man at the grave is left alone. It was all a dream. You played, but you were just playing a dream. In reality - in the game's reality - you never left the grave. And when you stopped dreaming, stopped playing, you are still standing there lost in grief.

Suddenly, it becomes apparent that Cavanagh has chosen an interpretation of the “don't look back”-motif that is very typical of our time: Don't look back in time! What has happened has happened and can't be changed! Seize the day! Be present in the moment! Etc. Therapy-style rationality, new-age style rationality, but not particularly well-aligned with human nature, our emotions, and our memories.

I don't know how mythologists traditionally explain the widespread occurrence of the “don't look back”-motif, but I believe that they interpret the specific use of the motif in the Orpheus myth as a tribute to Orpheus' humanity. He is human in his grief and his desire to turn back time. He is human in his hope to persuade the gods with his song and his love for Eurydice. And he is ultimately also very human in his eagerness to turn around to ensure that Eurydice is still behind him, forgetting the warning of the gods.

The gods, in contrast, are not benevolent therapists or wise mentors. They are petty narcissists who impose arbitrary and slightly nonsensical rules to demonstrate their power. They create unnecessary obstacles for humans and revel in cruel grandiosity by observing their troubles and struggles from above. Compared to them, Orpheus is a true hero in his determination to accomplish the impossible for Eurydice.

And the god in this game is none other than Terry Cavanagh. He is the one who creates the rules of the game. He is the one who punishes the player. The gods are petty and game designers are the pettiest of gods. The game designer's only task is to create an artificial obstacle course for the player – a heroic slave to the whims of the god. So, it's not surprising that Cavanagh would impose an arbitrary rule that condemns those who look back to death. It is in fact exactly what you would expect a game designer to do.

Therefore, the story and mechanics of Cavanagh's game align more closely with traditional mythologists' interpretation of the Orpheus myth than with the interpretation that Cavanagh himself presents in the game. That is a little ironic. Moreover, I think that the traditional interpretation aligns more with human nature than Cavanagh's modern-day moral lesson, which mostly just rings of unrealistic pragmatism.

But ultimately, these types of interpretations are interesting for mythologists, not for players, readers, listeners, or viewers. And although the final twist in Don't Look Back is a banal moral lesson, it is also the real virtue of the game. Eurydice may die, but at the same time we get a glimpse of how video games can breathe new life into clichés that are beyond saving in all other art forms.

When I experienced the ending, I felt like I was experiencing a twist of the same format and nature as the twists in movies like The Sixth Sense, Jacob's Ladder and The Others. But in reality, I was just exposed to the world's most trite and overused narrative device – the “it was just a dream” trope. No variation. No new angle. No addition. Simply: “it was just a dream.”

But it felt like more. It worked much better than in a movie. This was not because my expectations were lower due to the medium being a game, but because I myself played the dream. Because I myself acted in the dream, the dream felt so much more tangible and real. This amplified the shock when it was revealed to be just a dream.

Yes, like Hades and Persephone, game designers are petty narcissists, but they also possess the power to breathe new life into dead clichés.

Ola Hansson, 13 januari 2010

(English translation, 14 January 2023)

Other games by Terry Cavanagh

VVVVVV

Pathways

For another old-school platform game that flirts with Greek mythology and moreover explicitly portrays the game's designers as extremely petty deities, try Lighthouse Lunacy!