Profile of demands and tests for the short sprints

by Ola Hansson

Which qualities are required of a 100m sprinter and how are these qualities best tested? I will try to answer these questions at least fragmentarily and at the same time explain why I consider many traditional tests to be rather useless for the sprint trainer.

Profile of demands

As far as I know, the Swedish Athletic Association does not keep any official profiles of demands. In 1996, however, the Association’s journal Friidrott published a profile of requirements for most athletics events together with a series of articles and a one-off supplement concerning training theory. I don’t know who developed it, but the numbers are likely to have been compiled from old East German tables and not prepared by the Association itself.

In the profile of demands for 100m, the results in a number of tests are enumerated. As most of these tests are very close to the real event, the profile does not describe optimal, or even important, qualities for a sprinter. Neither do the test results serve as a guide for talent recruitment of children and teenagers. The actual purpose of the profile is never explicitly stated, but considering the relatively low result level of the test values I understand it as a list of threshold values that a sprinter with perfect technique have to achieve to even have a chance of reaching the goal result of the event itself.

This is the profile of demands for a 100m sprinter with the goal result 10.00 s:

| 200m | 20.00 s |

| 30m from starting blocks | 3.70 s |

| 30m from flying start | 2.65 s |

| 10 bounds from stationary start | 38–41 m |

| Half squat | 2.8–3.0 x body weight |

The 200m time I consider totally redundant. It’s tells you a comparable result in another, less competitive, sprint event, nothing else.

30m from starting blocks and from flying start are the most common tests for assessing shape during training periods. They are however so similar to the event itself that one could more or less run a full 60m or 100m race instead. That said, they do of course provide some additional and more specific information about acceleration and top speed.

10 bounds on alternating legs is also a common test that I find of questionable value since the bundle of physical qualities that is tested is almost identical to the bundle that is tested in a 100m race. Since the qualities are so similar, the test gives no additional information, and since there are several qualities, no specific information for any particular quality is provided (the main purpose of testing). Besides, I'd say that the technical performance plays a larger role in bounding than in running and because of this, it would actually be more reasonable to use 100m as a test for 10 bounds than the opposite!

Remaining then is the half squat. To lift 3 times your body weight seems like a legitimate lower limit if you are to be able to run 100m in 10.00. A typical sprinter of this calibre is likely to lift more than that, but if you lift less, 10.00 is probably beyond the limits of your physical potential.

The optimal sprinter

A profile of demands does not necessarily have to consist of merely a list of test results. One can also regard a profile of demands as an answer to the question: which are the most significant qualities required for an event? So which qualities should an optimal short sprinter possess? Here are my reflections and some suggestions.

Certain qualities are so obviously desirable and general for a large number of sports that they barely need mention. High testosterone levels to support a large amount of muscle mass as well as a low body fat percentage is one example; a strong immune defence that allows many and extended periods of continuous training is, together with an efficient nervous system, two others.

For the list of the optimal qualities I limit myself to those qualities that are less obvious, and particularly to those specific for 100m and not necessarily shared by other explosive sports of apparently the same character.

Antrophometry and physiological qualities

Nevertheless I will start out with a few thoughts about a quality I regard as trivial at most – height. It is worth mentioning since it is of great importance in so many other sports.

If a male 100m-sprinter is 1.60 or 2.00 m tall does not seem to matter for performances on elite level. Due to greater relative strength a short sprinter can start and accelerate somewhat faster, due to longer lever arms a tall sprinter can reach somewhat higher top speed. But when the distance is precisely 100m, the pros and cons seem to even out surprisingly well. After Usain Bolt’s fantastic feats in Beijing, there have of course been speculations about an evolution towards increasingly taller sprinters, but I believe future sprinters will remain a vertically varied crowd of pretty much the same average height as the rest of the population. Since qualities of an altogether other kind are much more significant than height and these qualities generally are normally distributed within the population – consisting of many more people of average height than of very short or very tall – the typical sprinter will remain at average height.

It is however advantageous to have legs that are long in proportion to the rest of the body (gaining you longer levers without depriving you of relative strength), and since tall persons usually have relatively, as well as absolutely, longer extremities one can assume that the optimal sprinter in practice will be somewhat taller than the average man.

Let’s move on then to the qualities that characterize the optimal sprinter:

- Slender hips – Cause less body rotation around the vertical axis and as a result a more efficient running stride.

- Wide shoulders – Neutralize body rotation more efficiently.

- Particularly well-developed proximal leg muscles (seat and thigh) – On the one hand they contribute the major force of the running stride, on the other hand their location on the lever arm minimizes the disadvantage of large mass.

- Relatively small or at least highly located distal leg muscles (calves) – On the one hand they contribute a minor force of the running stride, on the other hand their location on the lever arm maximize the disadvantage of large mass.

- A large amount of muscle mass evenly distributed all over the body – Large cross-sectional muscles with a high share of fast muscle fibres (type II a and II x) are the most fundamental requirements to get a body to move as fast as possible. The muscles in the lower part of the body generate the majority of the force of the movement, but powerful arm action is needed to counteract the rotation that arises. Other, not yet well understood, advantages of a well-developed upper body are in my opinion likely.

- Very little fat mass – Fat tissue diminishes relative strength and is thus particularly detrimental to acceleration.

- Legs that are long in proportion to the rest of the body – See above.

Battery of tests

Which tests you should use of course depends on the purpose. Is the purpose to

- recruit talent

- give short-term feedback on how specific qualities respond to training

- deduce an athlete’s state of health and need for recovery during a training period and before competitions

- analyse weaknesses and strengths for a long-term training plan?

The most common tests in Swedish athletics are – like those in the profile of demands from the journal Friidrott – tests that can identify a sprinter’s physical shortcomings or help deducing the causes of his current shape. But since the short sprints are technically and physiologically very uncomplicated sports, tests serve less of a purpose than in more complex sports where the relation between competition results and the qualities you train is considerably more complicated to determine.

Besides, results in the short sprints are measured objectively and are reached under standardized conditions with only psychological influence from your opponents. That’s a huge contrast to sports like football and wrestling and one could almost say that the short sprints of athletics, together with a few other sports like powerlifting, have more in common with tests than they have in common with other sports.

But there are of course tests that measure physical qualities that are even more basic and independent of technique than a 100m race. The following measures provide information that I consider both valuable and revealing beyond what can be learned from merely a 100m race time.

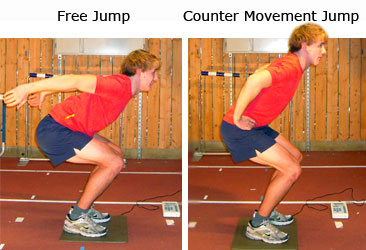

Vertical jump

Vertical jump results correlate strongly with squat results adjusted for body weight, but depend less on technique. And though you certainly can’t tell how fast an unknown individual will be able to run from his vertical jump, there is also a strong correlation between an individual’s improvement in vertical jump and the same individual’s improvement in 100m (the correlation isn’t perfect of course and that’s fortunate since it would make the test essentially meaningless). The vertical jump is a good measure of relative explosive strength which is probably the most crucial quality in the start and acceleration phase of a 100m race but less important when top speed has been reached.

Do I, as a coach, consider it vital, then, to regularly test my athletes in the vertical jump? No, it might be interesting to test newcomers; else it’s easy to keep yourself continuously informed by just being there during ordinary training sessions. Certain exercises, like for example 4 serial frog leaps also provide a good measure of relative explosive strength but at the same time serve as a good preparatory exercise at the start of a training session. When you train youths and pastime athletes you don’t have that much time at your disposal. To devote this time to a test that merely gives you a measure I find hard to justify.

Nor does it have to be a disadvantage that an exercise like 4 serial frog leaps is a bit more complex than a simple vertical jump on a timing mat as long as the extra qualities that are making themselves known are much less trainable than relative strength and therefore rather stable for each individual. But I can’t deny that serial frog leaps nevertheless require more technical skill than a single vertical jump and for this reason are less ideally suited for the pure task of testing.

Body composition

Talent – the genetic predisposition – is a major factor in the ability of a sprinter. Many key qualities just won’t allow themselves to be influenced. Other qualities are possible to have some bearing on but are of marginal significance. The amount of muscles and fat, however, are two of just a few qualities that are both easily influenced by training and do wonder for speed. Consequently, they should play a vital role in the training of a sprinter. But because of eating disorders and doping, reality is different. In Swedish athletics, at least, there is a tendency to play down the importance of muscle mass for strength – strength, the importance of which in addition is played down in favour of technique. Fat percentage is even more of a hush-hush subject – especially taboo to mention about, and to, female athletes.

This of course makes testing difficult. And, worse, it is usually also difficult to do something about too much flab and too little meat in spite of them being remarkably trainable attributes. Why? Because it is not always possible to be sincere to the athletes and you can’t control their diet during all the hours they spend outside the track and the gym.

In a way this is doubly ironic as most of the young sprinters and jumpers who would gain so much athletically by packing on some muscle and cutting some bloat, by way of perfectly natural vanity find the corresponding effect on their appearances just as desirable. When they instead spend their training on more or less meaningless routine exercises that neither affect competition results nor body in a positive way (but more often hurt the shins, knees and back) everyone except the greatest talent will obviously tire and give up on athletics.

Alright … As a conscientious coach I would find it useful to keep myself continuously informed about my athletes’ body weight and waist measure. But since that would have upset parents and an uneasy board of directors putting an end to my coaching assignments, I must instead let my eyes be my means of measurement. They are perfectly adequate for dealing with athletes who on the one hand have passed puberty and on the other hand have been training for a while so that you have learnt to identify their individual fat deposits. You do usually not even have to see the athletes in tanks and tights – the contour of the facial muscles should reveal enough about their current fat percentage.

One disadvantage of using your eyes as a permanently switched-on measure instrument is the tendency of unfavourable changes to occur gradually. When they one day are undeniably obvious, there may not be enough time left to do something about it before the race season.

Concluding thoughts

To sum up I identify quite a lot of problems in choosing tests for the short sprints. But if I had to carry out regular tests with the purpose of evaluating shape and gaining more specific information than provided by timing of a full 100m race, I would choose

- vertical jump

- body weight

- waist-measure

- 30m from flying start (under the condition that I have access to fully automatic time that is reliable and easy to administer.

My impression of Swedish athletics is that the tests carried out often provide a kind of illusory knowledge that in reality is meaningless to the coach but may offer welcome variety and serve as motivating informal competitions for the athletes. The tests can also work as pedagogical tools – “Now note that your vertical jump has increased 5 cm while your squat has improved 15 kg” – that convince the athletes that the training is meaningful and that the coach’s observations and explanations are correct. Unfortunately, it is common that the tests chosen are so dependent on technique that improved test results are rather due to improvements in technical skill than to improvements of the physical qualities you wish to measure.

On the other hand, I can imagine a lot of tests that would be of real benefit to the sprint coach – especially if the purpose is to get more than trivial information about current shape. I’d definitely consider information about health state, need for recovery and training sensitivity worthwhile and I suspect that there exists quite a few such tests (e.g. for hormonal markers, heart rate variability and sodium ions) that I lack knowledge about as well as equipment or resources for. To get precise information about how much larger training load the athlete can bear; to be able to measure a parameter during a training session, individual by individual, that tells you exactly how much rest each athlete would need until the next race for optimal training adaptation – such additions to the trainers arsenal I would warmly welcome.

Athletic Design, 28 April 2009 and 11 November 2009

An efficient running technique is of course also crucial. Se our high-speed video analyses for thoughts on that matter.